As the first President of the United

States of America stood before an admiring public in New York City to share his

thoughts on his inaugural day on April 30th, 1789, he said “There is no truth more thoroughly

established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an

indissoluble union between virtue and happiness.” Retired General George Washington then went on

to explain what his administration would be all about: “Our national policy will be laid in the powerful and immutable

principles of the private morality of its citizens”.

One of my favorite series of

lectures on our nation’s founding, given by Professor Daniel N. Robinson of

Oxford University is in fact titled American

Ideals: Founding a “Republic of Virtue”.

The

word virtue as used here, and understood by our founding fathers, referred to

the individual character of people willing to set aside self-interest in favor

of the daily living of Christian (Puritan) principles in the interest of “each

other”. For the founders, Robinson says, “there was an inextricable connection

among moral freedom, political liberty and that form of self-cultivation that

results in a person of virtue.”

From the first permanent English

colonies in 1620 to the first revolutionary gunfire at Lexington and Concord,

155 years of salutary neglect by Parliament had permitted American colonists

time and space to grow into a very different people than those first settlers

experimenting with self determination and local decision-making by common

consent. Reluctant revolutionaries though most of them were, circumstances

conspired to overcome a host of regional jealousies and cultural differences in

bringing together thirteen often-rival colonies in a loose confederation

unlikely – without a series of “miracles” – to incubate into a single nation.

That all of this happened –

including the “miracles” – amazed Europeans, watching from afar. It was this

curiosity which brought the young brilliant French scholar and attorney Alexis

de Tocqueville to the shores of the New World. Traveling with his friend Gustave de Beaumont, Tocqueville spends much

of 1831 and into 1832 visiting America’s cities and centers of government and culture,

and its small towns, villages and frontier fringes hoping to learn something

about that infant democratic experiment which might prove meaningful to the

“revolution” going on in France. His astute and far-reaching observations would

see light in his two-volume study, Democracy

in America, published in France in 1835 and 1840. (It has been said that

these works constitute “the best book ever about America”, and “the best book

ever about democracy”.)

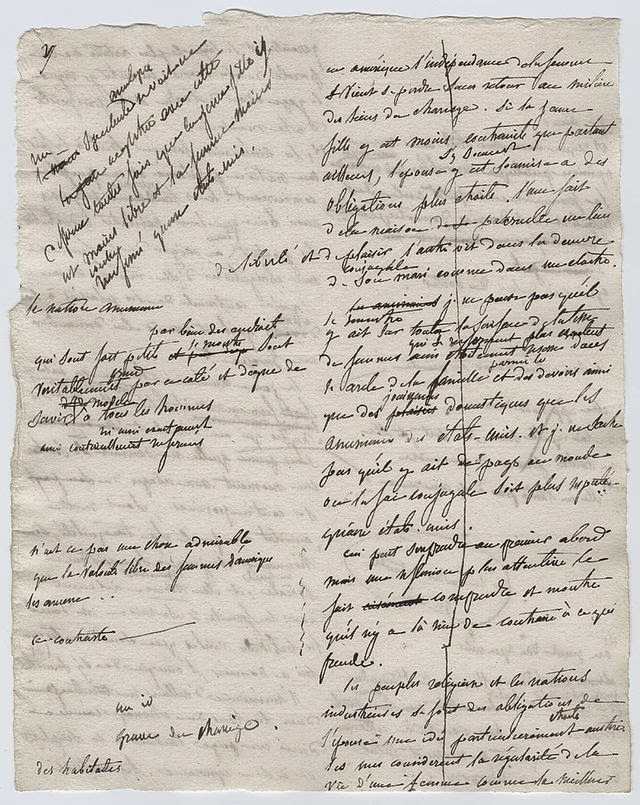

: Still intact today, an original hand-written

manuscript page of Tocqueville’s notes on 19th Century America. Courtesy Yale

University Rare Book Library

Among Tocqueville’s observations was

that in America, democracy trickled “up” rather than “down”, beginning with the

people, who were long accustomed to participating in local and regional

government up close. There, he opined that the jury system likewise played an

important role in familiarizing the population with the justice system in a

very personal way; virtually every adult having served on a jury and being

immersed in what we so oft-handedly describe as “the rule of law” at work. He

was further impressed by the presence of three important and revealing objects

he would find in every home he visited, whether a town house or a pioneer

cabin: an axe, a bible, and a newspaper. Americans were accustomed to hard

work, were invested in their religious faith and were educated and informed.

(Frontier Americans as a matter of fact read more books each year than their

“cultured” cousins in London by more than one account of the time.)

Tocqueville was quick to notice that

unlike European church-goers, Americans – regardless of specific denomination –

took their faith very personally, assuming the view that every person had the

right to speak to, and seek help and inspiration directly from their God. The relatively-smaller Jewish enclave in

the young Republic was no different.

In the end, the perspicacious Alexis

de Tocqueville doubted that the unique form of democratic freedom which had

developed in America could be easily duplicated anywhere else. And as we

observe one more Independence Day, it is worth reminding ourselves that most of

our founding fathers worried that with the feared growth of factionalism and a

diminution of that personal and individual morality Washington so cherished,

our Republic of virtue might one day itself be at risk.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, AMERICA!