When gold was discovered in California in the second half of the 19th century, a Bavarian-Jewish immigrant named Levi Strauss arrived in San Francisco in search of his own kind of “gold”. Following the lead of his New York family, he began supplying the hordes of newly-arrived miners with the dry goods they needed to carry on their pursuit, including work pants, often constructed from the same canvas material used in tents. Miners sometimes complained that the rough material chafed their legs as they worked, and tore too easily where seams met and pockets connected. One of Levi’s customers – a tailor named Jacob Davis - had an answer to the latter problem in the form of copper rivets he installed at these points of stress, along with double stitching on pockets and seams, becoming a partner with Strauss in making their reinforced “waist overalls” in a process earning U.S. Patent No.139,121.

The response to the chafing challenge was found with the introduction of a new and softer material shipped from the French port of Nîmes. For want of a more formal trade name, the fabric was known as “serge de Nîmes”, a moniker which would stick, even when manufactured somewhere else. And so, along with “dungaree” from India, “blue jeans” from Italy and the genius of two immigrants from Germany and Russia, the word “denim” from the French de Nîmes would join the very American lexicon of the times.

In 1885 a pair of Levi Strauss jeans, stitched by hand in the living rooms of women in their homes employed by the frugal partners, could be purchased for $1.50, and were popular almost entirely among working class laborers. By the beginning of the 21st century, those Levi “Jeans” would be selling for as much as $200 among the fashion-conscious, with a “second-hand” market pushing even those prices upward. Today Levi Strauss & Co .is the world’s largest brand-name apparel manufacturer with 38,000 employees in 49 countries around the world. In a typical year approximately 20 million tons of indigo will be produced just for the purpose of putting the blue in “blue jeans”.

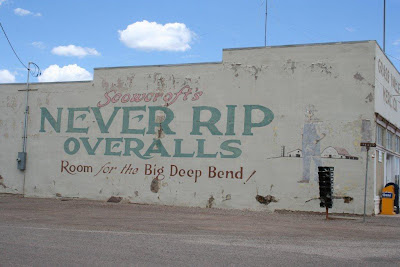

As far back as 1792, the term “overall” in early America described a protective, bib-and- brace garment favored by farmers and workers, often worn over the top of other clothing. During WW II, trousers made from denim became popular with women involved in war work, first in England and then the U.S., and a major clothing gender boundary had been crossed. This building sign is a surviving historic landmark in rural Utah.

Al Cooper photo

Double seam stitching and copper rivets became the patented hallmark of jeans made by the San Francisco entrepreneurs Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis more than a century ago.